From My Many Arms

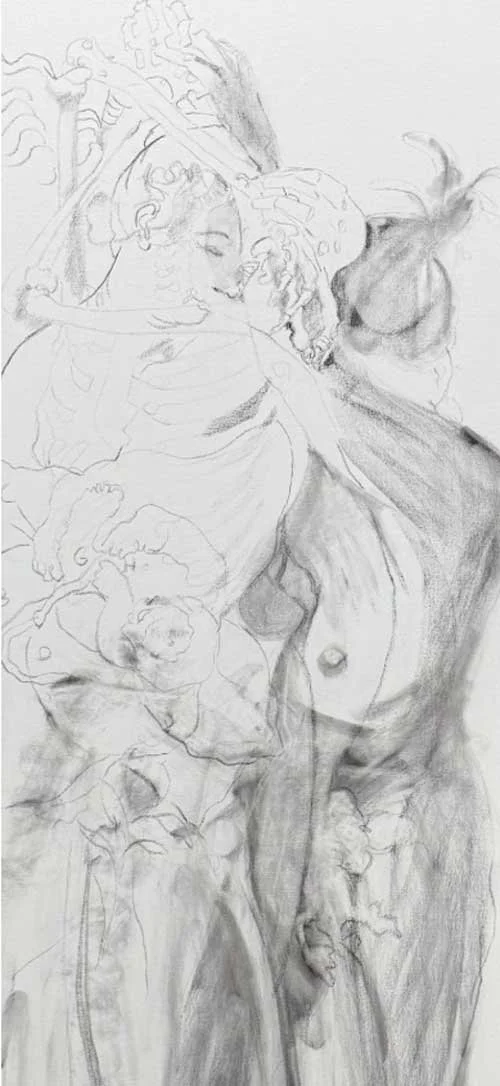

Detail of Mutable, Anatomia Inversa Series #1 of 9

I'm writing this by hand in a hotel room in Kerala, recovering from H1N1, watching gnats crawl across the page. A month ago I left my studio in Kentucky mid-series, nine large canvases of the Anatomia Inversa, my many-armed self-portraits built on Renaissance anatomical underpinnings. Now, fevered and far from home, I'm asking a different question: do those charcoal lines and bone-like brushstrokes reach toward something more universal than the Western tradition that taught me to make them?

Thank you, Ganesh. Did you give me this illness? Give me these moments of rest in return for that coconut, so that I could reflect on what I've learned from this land? From not only Hinduism, but the other philosophies that pervade this country. In India, I've been watching how philosophy isn't studied, it's inhabited. Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Christianity, they don't compete here, they breathe together in the same air, the same temples, the same bodies. For those who know it, it is easy to live, but they admit it is hard to understand.

My journey has taught me that you must break, even just a little, before you can begin to open to something new. It is necessary for wholeness.

The Meenakshi Temple in Madurai - Hindu devotion built atop Jain and Buddhist foundations, philosophy layered in stone.

Mirrored self-portrait with pure silver Gangajalis, commissioned by Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II in 1902. These vessels carried Ganga Jal or sacred water (900 gallons) from the Ganges river. Location: City Palace in Jaipur, India. They are remarkable examples of Indian craftsmanship and this image made me aware of the presence of myself in my works. All are likely portraits of the painter.

A rosary tree where faith finds expression in the simplest of devotional objects left behind by those seeking restoration. Saint Frances Mount Ashram Pattumala Matha Pilgrim Shirna, Kerala, India.

Consider that, for the Hindu, the infinite cannot be grappled with by the human mind in its totality. It is formless. So it reveals itself by taking many forms, personalities, and inhabiting stories to which we can relate. I've wondered whether, in my own work, I am getting at something similar, painting toward restoration via fragmentation?

When the three young girls danced in the temple courtyard, I watched the seven-year-old become Parvati in her multiple states, now gentle, now fierce, now dancing as Kali with her many arms extended. The girl inhabited the story as easily as breathing. It wasn't performance; it was how she understood why we anger, why we love, why we destroy, why we die. These subjects are important for me as an adult woman and artist, but I saw how essential they were for her too, a seven-year-old girl connecting to the unknowable through story, through her body, through dance.

I thought: I've been painting this. Those arms in my Anatomia Inversa, whose arms are they? Kali's arms that destroy ignorance and illusion? Or mine, reaching beyond what I thought I knew about Western portraiture and the singular self?

A young dancer after the Bharatanatyam Dance Group. The dance brings to life the mythological characters of divine origin which blends together music, rhythm, and poetry. I could see that she had studied hard to retell the stories that guide her religious beliefs, ultimately leading to an understanding of what it means to be human.

Sketch for Anatomia Inversa #2 Work in Progress. When I made these sketches I did not know the composite half female, half male imagery known as Ardhanarishvara representing the philosophical concept that ultimate reality transcends duality and contains all opposites in perfect balance.

Sketch for Anatomia Inversa #2 Work in Progress. When this painting began I was unaware of the symbology of the lotus, considered a sacred flower representing purity and enlightenment.

A bronze sculpture artisan creates replicas of traditional South Indian bronzes through the lost wax method. The design and construction of these artworks follow the strict aesthetic guidelines outlined in the Shilpa Shastra, an ancient treatise on Indian art. This artist working in Kumbakonam made an arm with the hand in the posture of Chin Mudra, symbolizing the merging of individual consciousness with universal consciousness.

Were my arms wrapped around something outside of Western portrait tradition when I began this series? The Western tradition celebrates the unique individual, the singular self. But what if I was reaching toward something more ubiquitous?

When I began, I did not know of Lakshmi emerging from a lotus. I did not know about Shiva-Parvati as one being, half-male and half-female, Ardhanarishvara. I thought the duality presented by the one-sex model in our pre-18th century Western tradition was something to be challenged. I was interrogating how male and female had been presented as unequal, separated by a dominant narrative.

But I kept encountering Ardhanarishvara in the temples—Shiva and Parvati merged into one being. At first I saw it through my Western lens: here was another culture wrestling with the problem of duality. But that's not what I was seeing at all. The priests explained it plainly: Shiva without Shakti is consciousness with no energy to manifest. Shakti without Shiva is chaos without form. They need each other to create anything. Not opposition. Not hierarchy. Necessary interdependence.

Now I understand that duality is ultimately illusory.

For some time now, my work has crossed into the universal and archetypal. The faces and figures contain multitudes. They are vessels for some larger force, forces with which I am much more familiar after a month in India. I realize now that the second painting in my series of nine holds something I could not know in my limited Western training. I could not see it from my studio.

Here, however, the forces are painted purple and pink and yellow, not always colors made from the earth, but colors we invent. Colors that we then impose upon ourselves, upon others, and upon monuments centuries old. The forces are here just behind me in the clanking of utensils on porcelain plates and the gnats that keep crawling over this page.

To travel through India is an invitation to let these forces do more than prod. India slams them up your nose, in your ears, eyes and intestines. You crack open and see that others have the very same cracks. Something is destroyed: what you thought you knew, especially about the self.

You can walk barefoot through the temples with temperatures over 100 degrees and stone floors burning your feet, because your feet are stronger for all of the flesh that has crossed the same threshold. Socks are a thin barrier where reverence is divine and you feel an infinite reality pressing up through you.

I had to look again at the Anahata Chakra symbol—it is a six-pointed star formed by two interlocking triangles. The upward triangle represents masculine energy, consciousness, and fire. The downward triangle represents feminine energy, creation, and water. The lotus in the center represents divine union and spiritual awakening.

I don't completely understand yet, but I think I can live it now. I can bring this back to those nine unfinished canvases, the profoundness of what has soaked through my skin and into my heart on this journey. Not to appropriate, but to recognize what was already stirring in the work before I had names for it.

I'm ready to return to my studio and employ my many arms.